Kevin S.Y. Tan, 1 July 2024

Whenever one speaks of the concept of community, we tend to associate this with specific places where persons live, and they often call it home. However, this is not always the case, especially in a post-place world, where innumerable virtual communities now reside within digitized environments. However, there are communities that are neither of these categories, such as communities connected by shared interests or circumstances. These communities may be associated with specific places but are not necessarily bounded by them.

One example of such a community is found at Waterloo Street in Singapore, where two of the country’s most historic religious sites are located. Along this street are two temples, one of Hindu origin known as the Sri Krishnan Temple, and the second, a Chinese temple known as the Kwan Im Thong Hood Choo Temple (or Kwan Im Thong, for short). The former is a temple dedicated to the Hindu god Krishna, while the latter houses the Chinese deity, Guan Yin, also known as the Goddess of Mercy.

Both temples originated along Waterloo Street in the late 19th century during Singapore’s colonial past and are the legacy of migrant diasporas during that era. Kwan Im Thong was built in 1884, while Sri Krishnan Temple is even older, emerging in 1870. Together they form a unique inter-cultural and inter-religious enclave close to the city centre of Singapore. For example, devotees of Kwan Im Thong often visit Sri Krishnan Temple after their initial prayers at the former.

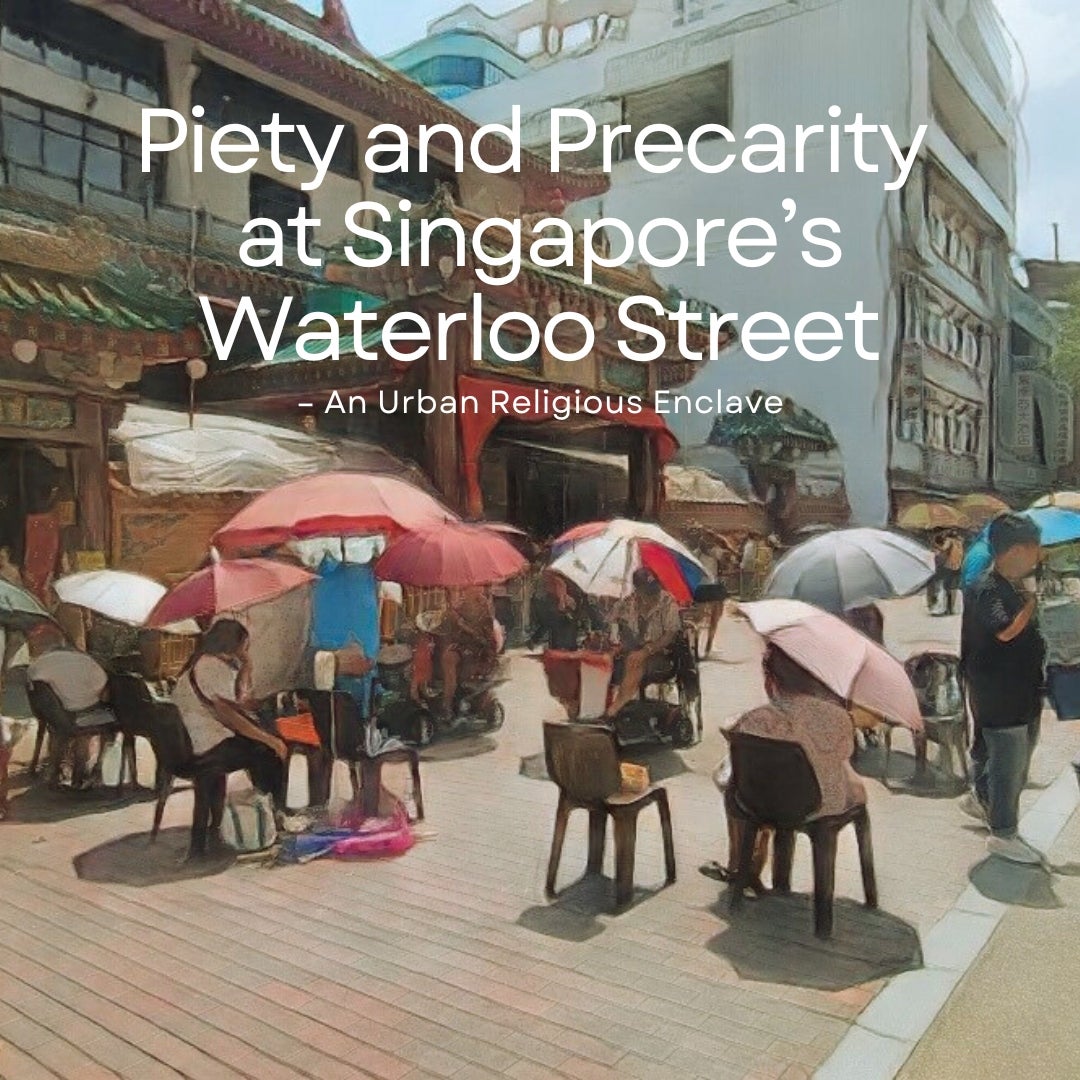

Having visited Kwan Im Thong regularly with my parents in my youth, I remain struck by how much the immediate social and physical environments around these two temples have transformed. In 1998, part of Waterloo Street was converted into a pedestrian walkway to enable easier mobility for visitors. This is because Kwan Im Thong attracts thousands of devotees each day, while the older Sri Krishnan Temple, although more modest in terms of human traffic, remains an important site for local Hindus on important religious occasions. Converting the immediate road in front of both temples into a walkway was a practical decision, as the heavy human traffic posed complications to pedestrian safety, particularly during festive occasions like Vesak Day or the Lunar New Year. The ensuing years have led to the gradual evolution of an urban enclave that exudes a unique character.

The site is surrounded by a combination of ageing private apartment buildings and a HDB residential estate that contains a wet market and food centres serving affordable local food. Dozens of vendors line the walkway in front of Kwan Im Thong, selling flowers and joss sticks to devotees and some have been plying their trade for at least four decades. In recent years, a corresponding religious economy around the temples has emerged, where several businesses have also set up quasi-temples or shrines dedicated to various Chinese or Indian deities. Within nearby ageing malls like Fortune Centre and Fu Lu Shou Complex, there are numerous shops selling religious paraphernalia and a few restaurants offering vegetarian meals, a diet practised by many devotees.

As one explores the T-shaped pedestrian walkway, one can observe several “spiritual specialists” that assist in interpreting divination lots, the occasional street-level traditional healer providing affordable therapeutic massages, and transient discount stalls selling clothing, tools, and sundries. They stand in contrast with the more conspicuous foreign employees of several beauty and massage shops that line one side of the street, who aggressively tout their services to pedestrians.

A lesser-known fact is that Waterloo Street was once the site of numerous street beggars. I recall seeing them from my childhood in the 1970s and 80s, where many sat near the entrance to Kwan Im Thong as devotees entered the temple with their offerings of fruits, flowers and joss sticks. Today some claim there are no more beggars, but that is from a certain point of view. What you do see instead, are dozens of elderly and disabled vendors near both temples along the pedestrian mall. Most are selling packs of tissue paper and lottery tickets, and their relative poor health and income insecurity is often visible due to their poor mobility and somewhat ragged dressing. Perhaps the tissue or lottery ticket selling industry is nothing more than a visual euphemism for present day street-level begging for a growing precariat in Singapore. One further recalls how the entrance of Kwan Im Thong can be particularly crowded on weekends with volunteers from charity-based or non-profit organizations, seeking donations as part of a broader “industry of compassion”.

If we extend our ethnographic sensitivity through keen observation, we will notice how this urban religious enclave is often frequented by the less privileged, the marginal and the low-income elderly. Wheelchair-bound persons, the sickly and migrant workers are often seen and heard in the vicinity. This apparent link between piety and social-economic precarity is one of the most compelling characteristics of Waterloo Street’s urban religious enclave, as it stands in contrast with the tourism-driven and consumerist Bugis Junction Mall barely a hundred metres away, just across Victoria Street. It is also revealing of how this community of circumstance at Waterloo Street exists in a very different lived reality from other parts of Singapore. Their presence suggests a possible correlation between the dominant religious worldviews at Waterloo Street and certain social-economic backgrounds.

Such a connection reveals the importance of Waterloo Street as a religious resource for the persons who frequent it, but this relationship is more than just about religious expression or devotion. It is implicative of a deeper interpretive role that Kwan Im Thong and Sri Krishnan Temple perform for less visible sectors of Singaporean society be they citizens or transient residents. One also notices a certain historical continuity with the past, when similar migrant and underprivileged communities to Singapore contributed to the founding of both temples due to shared needs and lived experiences. In a society where the narrative of development and progress tends to highlight change and the removal of the old in celebration of the new, Waterloo Street’s religious enclave remains a liminal-like bulwark, for now, against such forces. Perhaps this enclave has the capacity to slow one’s perception of time while enabling a space for those who feel ‘out of place’ elsewhere, allowing many to obtain some measure of meaning, comfort, and hope.

Kevin S.Y. Tan is a cultural anthropologist and lecturer at Chua Thian Poh Community Leadership Centre at the National University of Singapore. His research interests include urban enclaves, borderlands studies and ageing societies. (All images are the personal property of the author)